Will Letter Grades Survive?

A century-old pillar of the school system is under fire as schools look to modernize student assessment.

Under pressure from an unprecedented constellation of forces—from state lawmakers to prestigious private schools and college admissions offices—the ubiquitous one-page high school transcript lined with A–F letter grades may soon be a relic of the past.

In the last decade, at least 15 state legislatures and boards of education have adopted policies incentivizing their public schools to prioritize measures other than grades when assessing students’ skills and competencies. And more recently, over 150 of the top private high schools in the U.S., including Phillips Exeter and Dalton—storied institutions which have long relied on the status conveyed by student ranking—have pledged to shift to new transcripts that provide more comprehensive, qualitative feedback on students while ruling out any mention of credit hours, GPAs, or A–F grades.

Somewhat independently, schools and lawmakers have come to the same conclusion: The old models of student assessment are out of step with the needs of the 21st-century workplace and society, with their emphasis on hard-to-measure skills such as creativity, problem solving, persistence, and collaboration.

“Competency-based education is a growing movement driven by educators and communities focused on ensuring that students have the knowledge they need to flourish in a global economy,” said Susan Patrick, chief executive officer of iNACOL, a nonprofit that runs the website CompetencyWorks. “The future of jobs and the workforce will demand a new set of skills, and students’ capacity to solve complex problems for an unknown future will be essential.”

For their part, colleges—the final arbiters of high school performance—are signaling a surprising willingness to depart from traditional assessments that have been in place since the early 19th century. From Harvard and Dartmouth to small community colleges, more than 70 U.S. institutions of higher learning have weighed in, signing formal statements asserting that competency-based transcripts will not hurt students in the admissions process.

The emerging alignment of K–12 schools with colleges and legislators builds on a growing consensus among educators who believe that longstanding benchmarks like grades, SATs, AP test scores, and even homework are poor measures of students’ skills and can deepen inequities between them. If the momentum holds, a century-old pillar of the school system could crumble entirely, leading to dramatic transitions and potential pitfalls for students and schools alike.

PICKING UP STEAM

Scott Looney, head of the Hawken School in Cleveland, was frustrated. His school had recently begun offering real-world, full-day courses in subjects like engineering and entrepreneurship, but he was finding it difficult to measure and credit the new types of skills students were learning using A–F grades. Looney started reaching out to private high schools and colleges looking for alternatives.

Though he found that many educators shared his desires for a new assessment system, he came up empty-handed.

“The grading system right now is demoralizing and is designed to produce winners and losers,” said Looney. “The purpose of education is not to sort kids—it’s to grow kids. Teachers need to coach and mentor, but with grades, teachers turn into judges. I think we can show the unique abilities of kids without stratifying them.”

Looney began brainstorming a new type of transcript for the Hawken School, but quickly realized he would need a critical mass of schools to influence college admissions offices to accept it. With the initial support of 28 other independent schools, Looney formed the Mastery Transcript Consortium (MTC) in April 2017. The group has since expanded to 157 schools, including both historic institutions like Phillips Exeter and newer alternative schools like the Khan Lab School.

In joining the MTC, each school commits to phase out its existing GPA- and grade-based transcripts for a digital, interactive format that showcases students’ academic and enrichment skills, areas for growth, and samples of work or talents, such as a video of a public speaking competition or a portfolio of artwork.

While the transcript is still in its infancy, organizers say it will resemble a website that each school will be able customize by choosing from a menu of skills like critical thinking, creativity, and self-directed learning, along with core content areas such as algebraic reasoning. Instead of earning credit hours and receiving grades, students will take courses to prove they’ve developed key skills and competencies. Looney insists that the transcripts will be readable by admissions officers in two minutes or less.

The MTC’s work is not entirely original, though, and takes its lead from a number of public schools—most notably in New England—that have been rethinking traditional methods of assessing students for more than a decade.

Some are supported by the nonprofit group Great Schools Partnership, which helped influence Maine, Connecticut, Vermont, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire to adopt state board of education policies or legislation in the last decade on proficiency-based assessment systems. Other districts, in Florida, California, and Georgia, have made similar changes more recently, and pilot programs have emerged in Colorado, Idaho, Utah, Illinois, Ohio, and Oregon.

There’s also backing from colleges. The Great Schools Partnership was able to garner the support of more than 70 colleges and universities, suggesting that higher ed admissions offices are ready for the change.

“We are accustomed to academic reports from around the world, including those from students who have been privately instructed and even self-taught,” said Marlyn McGrath, Harvard University’s director of admissions, replying via email about the transcripts. “In cases where we need additional information, we typically ask for it. So we are not concerned that students presenting alternative transcripts will be disadvantaged because of format.”

MASTERY VERSUS SEAT TIME

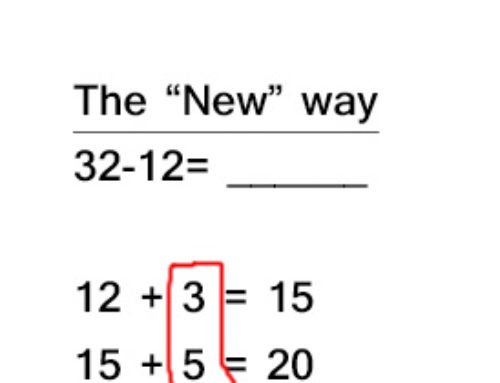

But the new transcripts are just the tip of the iceberg, according to supporters, part of a larger movement to do away with a system where kids can progress through grades or courses without really understanding material and be promoted for seat time and good behavior. When students move on to harder topics, they continue to accumulate gaps in their knowledge—a setup for failure in the later grades or collegiate years.

Under a competency model, kids can no longer just “get by,” said Derek Pierce, principal of Casco Bay High School in Portland, Maine, which has used a proficiency-based transcript since 2005.

The new transcripts “get kids focused on doing their personal best on meeting or exceeding standards rather than getting a better grade than the kid next to them,” said Pierce. “There is no longer a ‘gentleman’s C’.”

However, without widespread agreement on the necessary skills and knowledge required for core classes, proving mastery may be just as elusive and arbitrary as the current system. Even MTC member schools won’t rely on a shared understanding of what mastery means. Instead, each school will be able to quantify it independently, leaving college admissions officers—according to critics—without a clear basis of comparison.

While competency-based education proponents argue that the new transcripts will identify students with skills that academia has traditionally overlooked, others worry about equity for marginalized students, who already struggle in the current system. Some critics have suggested that the new transcripts may be a way for wealthier schools, especially private schools like those in the MTC, to give their students an even greater advantage when competing for limited positions at the best universities.

There are other unanswered questions and challenges to be worked out, too. Will college admissions counselors have enough time, especially at large public colleges, to look meaningfully at dense digital portfolios of student work? Will the new transcripts create too much work and new training for K-12 teachers, as they struggle to measure hard-to-define categories of learning? Perhaps most importantly, will parents buy in?

“There’s still plenty of work ahead and some pretty radical changes taking place,” explained Mike Martin, director of curriculum and technology at Montpelier Public Schools in Vermont, whose district starting transitioning to a competency-based model in 2013.

Many public and private schools, like Martin’s, are still years away from full implementation, and others are grappling with the nuts and bolts of how to implement dramatically new systems for student learning and assessment. Those on the forefront of these changes, though, remain hopeful that the new system will push all students to develop the skills they need to succeed in college and careers.

“Our learning structures have to be much more nimble to allow today’s learners to navigate through opportunities where they can see themselves as the authors of their education,” said Martin. “Proficiency-based education is about getting every single student up to a certain skill level and ensuring every student can succeed.”

Source: https://www.edutopia.org/article/will-letter-grades-survive